Sep 12, 2007

Posted | 0 comments

The 136th Carnival of Education is online at History is Elementary - it’s got dozens of excellent posts on teaching, policy, higher education and, really, all things school. It seems like the CoE gets better by the week.

The 89th edition of the Carnival of Homeschooling is live at Why Homeschool. It’s the soccer edition - how our hosts managed to work so many posts into a coherent soccer theme is nothing short of a work of art.

And don’t forget to take a look at Secondhand Thoughts’ Wednesday website. This week’s edition showcases Journeys, a site that I’ve had in my RSS reader and blogroll for a while now. It’s a great selection - the perspective Diane provides from the library/media standpoint is a welcome addition to my daily reads. She’s certified in New York, so I may be biased… but I doubt it. Add her and give a read - you’ll likely agree that it’s good stuff.

Sep 11, 2007

Posted | 12 comments

The Journal of Common Sense in Education has a new submission ready for peer-review: rightly or wrongly, appearance is a factor. I can’t be too bothered when I read about wasted time and resources dedicated to questions that could be answered properly by anyone who has a) left their home in the last 20 years and/or b) has firing neurons. Why?

Because I’m pleased that third-rate researchers are putting time into trivial subjects instead of mucking up research that actually matters. It’s the lesser of two evils.

EdWeek hops on the bandwagon:

Researchers Julia Smith of Oakland University in Rochester, Mich., and Nancy Niehmi of Nazareth College of Rochester, N.Y., analyzed test results and other data for nearly 9,000 boys across the country who started kindergarten in 1998. They found that kindergarten teachers systematically perceived boys who were shorter than average—or even just shorter than the other boys in their class—to be less skilled in reading, mathematics, and general knowledge than their test results indicated.

Well done.

Then BoardBuzz, the blog of the National School Boards Association, sees EdWeek’s float pass by in that daily parade of irrelevant education research and says, “Hey guys, wait up!”:

No wonder Napoleon had a complex

File this tidbit from Education Week under Huh? It turns out, according to a report in the Journal of Educational Research, “Kindergarten teachers typically underestimate the intellectual abilities of boys who are shorter than their classmates.” As if being really short wasn’t bad enough.

All kidding aside, the report …

[summary quote]

Try telling that to such diminutive dynamos as Danny DeVito (5′), Prince (5’2″), Paul Simon (5’2″), and Willie Shoemaker (4’11″).

Yes, I understand that they’re trying to be funny. And yes, I also understand that jokes in education coverage out of necessity tend not to be gut-busters.

But I’d like to make a few points about the inappropriate/inaccurate reference to Napoleon:

- Napoleon was, as far as we can tell, a man of above-average height compared to Frenchmen of his era. About 3 minutes into any responsible History 101 course, you’ll hear something about the fallacy of evaluating people/events in history by today’s standards - committing that fallacy perpetuates dumb myths like this one.

- Napoleon was ~5’2″. Short, yes? Depends on whose inches you’re referencing. The French inch at this time corresponded to 2.71cm while the British Imperial inch was 2.54cm. Though history suggests that Napoleon, at the time of his death, would’ve been measured with a British stick [after all, the British were holding him when he died] we can’t be sure. And I, personally, can’t be sure, either - I wasn’t there. But is it possible that someone just referenced a previous measurement without realizing a .17cm difference in units that would amount to a 4″ discrepancy? Far stranger things have happened.

- Le petit caporal, Napoleon’s nickname, is an affectionate term that denotes brotherhood. It shouldn’t be translated into English as meaning “little” as “Le Petit Prince” does.

- Napoleon was often accompanied by his elite guard, all of whom were 6′ or taller. Even a man of above-average height would look pretty small when surrounded by relative giants.

- Napoleon ultimately lost and years of European warfare made a comfy bed in which a negative Napoleon myth could rest. Though I find the “history is written by the victors” attitudes professed by Comrade Zinn and others to be inappropriate and agenda-driven, it isn’t hard to justify some of the creation and perpetuation of the Napoleon height myth in this way.

Wikipedia, that darling of the progressive educator, compiles some references for these points. Numbers 1, 3 and 4 are solid; numbers 2 and 5 are speculative.

The most intriguing irony with BoardBuzz’s point is that if there is a valid, well-understood Napoleon complex - and I think there probably is, it’s just got the wrong name and need not be confined only to height - that results from one’s perception of inadequacy by others, then logically we can conclude that we’re aware that others might treat a shorter person differently. If they didn’t or it wasn’t a possibility, there wouldn’t be a Napoleon complex reference that fit the headline requirements of this article. And, if that’s the case, this groundbreaking research tells us something we already know [or should know] that has a strong enough foundation to make for a cruddy, barely-humorous title reference.

Keep in mind, researchers and their benefactors - as you fritter and waste time telling us what we already know, there are quite a few kids out there who still can’t read.

But maybe I’m wrong and there really aren’t more pressing issues out there. And at the least, we’ve got a lesson on why it’s important that educators get a little more substance to go along with their teaching methods and school leadership courses.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Sep 11, 2007

Posted | 0 comments

This is an education site - not a political site - so I’ll be brief.

I don’t use the phrases “9/11″ or “September 11.” Instead, I refer to the events 6 years ago today as what they were - a terrorist attack on the World Trade Center, the Pentagon and the United States - rather than focusing on when they happened. That they happened on a certain day is an irrelevant detail.

I understand that “9/11″ and the like are shorthand; it’s a convenient way to sum up a complex issue. But I don’t bother with the day for the same reason I don’t say “December 25″ when I really mean Christmas.

I won’t use a particular day to ponder something so relevant and important to our daily lives. I tend to relegate thoughts about the Battle of Gettsyburg to early July because, at this stage in America’s history, its daily significance has passed. But the effects of the WTC and Pentagon terrorist attacks are currently as important on September 10, September 12 and every other day as they are on the 11th and in no way will I pretend that they aren’t.

It does a disservice to the commitment of every serviceman and supporter of our efforts to regard this day with much more importance than any other day; a man who showers his wife with love and attention only on their wedding anniversary doesn’t have much of a marriage at all. If you ask me how I feel about the WTC/Pentagon attacks, you’ll get the same answer today as you will a month from now.

Mark Steyn has reprinted his September 12, 2001 column called “A War for Civilization” and added a bit of perspective - it demands a careful read.

And a note from my personal archives:

Sep 10, 2007

Posted | 9 comments

CaliforniaTeacherGuy has gotten deserved attention for his rejection of a phrase his students - and really, everyone’s - use too often: “I don’t know.” Joanne Jacobs picked up on his thoughts and even EdWeek’s BlogBoard has rightly turned a keen eye to CTG’s commitment to “Outlawing Fear.”

I wrote a lengthy comment on his site last night, got distracted near the end, navigated away from the page and *poof* - gone. I’ll address it here instead.

CTG writes:

“Many of my students are so afraid of making mistakes that they don’t even try to formulate intelligent responses to my questions. When I ask them their opinion about a poem or a story we have just read, they automatically reply, “I don’t know.” They seem to think that thinking is too hard, and “I don’t know” is an easy way out.”

It isn’t news that ignorance is a crutch on which too many rest too often. I thought so much of CTG’s article because I appreciate his refusal to accept the complacency that plagues a disinterested generation. That disinterest is justified by “I don’t know” and encouraged by its acceptance; CTG is taking steps to remedy both of these problems. I’d like to weigh in on the proposed replacement for “I don’t know,” which is, “I’m not sure, but I think…”

The basic argument against “I don’t know” is that it stems from a student’s fear of thought and fear of being wrong. These two conditions are an unfortunate reality for many students. Those two fears, made worse by many students having been ill-equipped to overcome them, push and pull at a mind that fatigues quickly and produces, “I don’t know.” It’s a shot of intellectual morphine for an ailing mind.

Most every time I’ve replied, “I don’t know,” it’s because I haven’t taken the time to think about the issue or haven’t put the time into researching it. Occasionally I’ll do both and still not know, but then the “I don’t know” is followed by an explanation of why I still don’t know. That’s why we need to replace, “I don’t know” with:

“I haven’t thought about it yet.”

The admission that one hasn’t thought about a topic is an important step toward erasing the “I don’t knows.” It isn’t meant to shame a student; instead, it recognizes the reality of the student’s response to a situation. Saying that one hasn’t thought about it conveys two things: 1) An honest assessment of why there isn’t an answer and 2) recognition that if one thinks about the question at hand, they’ll have an answer. Asking the question defines the problem; points 1 and 2 show a student how to go about it.

“I’m not sure, but I think…” and its variants convey a relativism that is inappropriate for most contexts in education. We need to fill our students with the confidence and tools to answer a question; starting a response with an admission that undermines its certainty and uses a justification of its value based simply on the fact that it has been thought can become as much of a destructive crutch as “I don’t know.”

“I haven’t thought about it yet” or, as Darren relates from his time at the Naval Academy, “I’ll find out,” supports the education that we’re charged with delivering. It recognizes the problem at hand, focuses on the responsibility to solve it and then commits to that process. It’s an honest, transparent and productive way to handle a question.

Sep 9, 2007

Posted | 2 comments

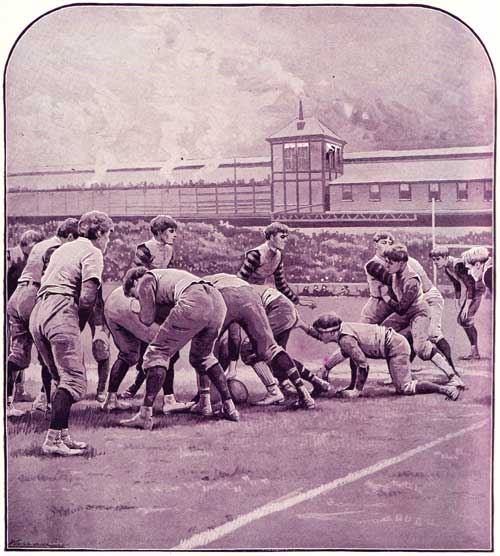

I scanned the following illustration from John Clark Ridpath’s Royal Photograph Gallery published by B. F. Johnson & Co., 1893. A fine piece of Americana for a Sunday afternoon.

Image text:

FOOT-BALL.-PUTTING THE BALL IN PLAY.-The great national game of base-ball is played in summer; interest in foot-ball culminates in the strenuous struggles by college boys on and before Thanksgiving Day. Thus far England is ahead of us in the popularity of foot-ball and in the number of fractures, mutilations and deaths resulting from its indulgence; but the widespread excitement caused by a contest in America seems prophetic of our probable future equality with our English cousins in this form of sport, which, spite of the little drawbacks mentioned, has much to recommend it. Rough, it is also manly-no milksop can be a foot-ball player; and it necessitates in the adept the exercise of sound and ready judgment, as well as fleetness, purpose and agile strength. Gambling and professionalism are abuses which good friends of the game should do all they can to discountenance.

This tome includes 400+ full-page photographs and illustrations of everything from Bedouin Sheikhs to London Bridge. You can get a copy via AbeBooks for around $7 USD.